BY: KATHLEEN LEW

|

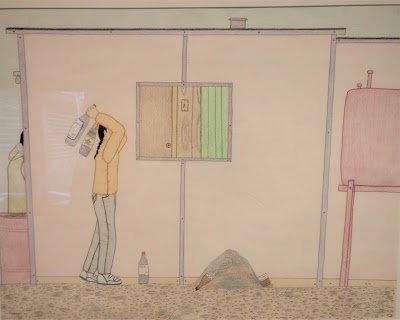

| Annie Pootoogook, Bringing Home Food, 2003-2004. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

I first discovered the art of Annie Pootoogook in 2015, during an undergraduate Indigenous Art History course at Queen’s University. I was immediately drawn to her honest depictions of life in the North, whether it was watching television, eating with family, exploring her sexuality, or drawing experiences of abuse and addiction. I wrote my course paper on Pootoogook and her contentious place in both understandings of Inuit authenticity, and contemporary art.

Following my initial research, I came across articles about Annie’s life in Ottawa, but felt uncomfortable reading her struggles as headlines. Reporters were intruding on the artist’s personal life, and I was torn about how to interact with her career. When Annie was found dead in the Rideau River in September of 2016, I witnessed how my surrounding community mourned the loss of the artist. This was most visible through a student article in the Queen’s Journal, and statements from the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, who had shown a solo exhibition of Pootoogook in 2011.

Years later, I am still grappling with my admiration and knowledge of Pootoogook’s art. This time, it is in the context of a masters course on Museums and Indigenous Communities at the University of Toronto, and a visit to the first retrospective exhibition of Pootoogook since her death, McMichael Canadian Art Collection's Annie Pootoogook: Cutting Ice, curated by Nancy Campbell.

The same question remains as it did a year ago: How can I remember Annie Pootoogook?

There are many perspectives, including voices from the Kinngait community, Pootoogook’s colleagues in Toronto, art historians, and the press. Remembering is an active process, and like her art, we should honour Pootoogook within her complexities. It is impossible to approach Pootoogook's career just from her drawings, her biography, her womanhood, her place in the Canadian art world, or the larger systemic oppression of Inuit peoples in Canada. We must understand how these approaches intersect.

Following my initial research, I came across articles about Annie’s life in Ottawa, but felt uncomfortable reading her struggles as headlines. Reporters were intruding on the artist’s personal life, and I was torn about how to interact with her career. When Annie was found dead in the Rideau River in September of 2016, I witnessed how my surrounding community mourned the loss of the artist. This was most visible through a student article in the Queen’s Journal, and statements from the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, who had shown a solo exhibition of Pootoogook in 2011.

Years later, I am still grappling with my admiration and knowledge of Pootoogook’s art. This time, it is in the context of a masters course on Museums and Indigenous Communities at the University of Toronto, and a visit to the first retrospective exhibition of Pootoogook since her death, McMichael Canadian Art Collection's Annie Pootoogook: Cutting Ice, curated by Nancy Campbell.

The same question remains as it did a year ago: How can I remember Annie Pootoogook?

There are many perspectives, including voices from the Kinngait community, Pootoogook’s colleagues in Toronto, art historians, and the press. Remembering is an active process, and like her art, we should honour Pootoogook within her complexities. It is impossible to approach Pootoogook's career just from her drawings, her biography, her womanhood, her place in the Canadian art world, or the larger systemic oppression of Inuit peoples in Canada. We must understand how these approaches intersect.

| |

| Annie Pootoogook, Red Bra, 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Remembering Poootoogook as a great Canadian artist is one step, but I think there can be more action. We can ask how to remember Pootoogook, and continually improve these methods of remembering. By framing her legacy as a question, we can grapple with the significance of her life and work over time.

So here is my working list, one that will inevitably change. My attempt to answer the question—how can we remember Annie Pootoogook? The following list is what I have learned from Annie, and what I can continue to learn through her art.

1) See beauty and significance in the mundane.

So here is my working list, one that will inevitably change. My attempt to answer the question—how can we remember Annie Pootoogook? The following list is what I have learned from Annie, and what I can continue to learn through her art.

1) See beauty and significance in the mundane.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Ritz Crackers, 2004. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook drew life in Cape Dorset, showing viewers the simplicity of moments at home, and the significance of everyday objects. It could be ingredients for making Bannock, a box of Ritz crackers, a pair of scissors, or her grandmother’s glasses—all were given importance and care. Pootoogook demonstrates the value of documenting tradition, the present, and how they work together.

“Annie’s work is very different. Annie’s work is, like today and yesterday and…daily happenings, shopping, music, the feast. Sometimes she will draw very hurt feelings from her heart which she’s not afraid to say on paper.” – Jimmy Manning, manager at Kinngait Studios

“Annie’s work is very different. Annie’s work is, like today and yesterday and…daily happenings, shopping, music, the feast. Sometimes she will draw very hurt feelings from her heart which she’s not afraid to say on paper.” – Jimmy Manning, manager at Kinngait Studios

2) Create to heal.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001-2002, Photo Courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook’s drawings of anguish communicate Indigenous realities of addiction, mental illness, and violence. By drawing her memories on paper, Pootoogook could begin to make sense of her experiences from a distance. At the same time, these depictions force viewers to confront the hardships of Inuit communities.

“It seems that I throw that shit out of my mind and start drawing. Well, drawing makes me feel better… better a lot than before.” -Annie Pootoogook

3) Embrace sexuality.

“It seems that I throw that shit out of my mind and start drawing. Well, drawing makes me feel better… better a lot than before.” -Annie Pootoogook

3) Embrace sexuality.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Woman at Her Mirror (Playboy Pose), 2003. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook was unafraid to depict the body, using drawing to explore herself and her relationships. Through art, Pootoogook legitimizes female and Indigenous sexuality, challenging the viewer’s discomfort of gender and sexual identities that are considered "other".

4) Support and celebrate our family, friends, and communities.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Pitseolak Drawing with Two Girls on her Bed (detail), 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook’s practice was largely influenced by her family and her community. Pootoogook continually celebrated Pitseolak’s influence in her drawings, signified by her grandmother's black-rimmed glasses. Pootoogook’s career began with support from the Kinngait Studio, an artist community that creates prints for the Inuit art market. Pootoogook used the influence of her ancestors and community to chronicle her own surroundings and experiences.

5) Listen to contemporary Inuit voices.

5) Listen to contemporary Inuit voices.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Dr. Phil, 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook challenged assumptions of Kinngait as a pure, untouched North. She demonstrated the presence of Western influence, and the unique hybrid identities of Inuit artists. Nancy Campbell works to include community voices with Cutting Ice, exhibiting artists influenced by Pootoogook, such as Ohotaq Mikkigak, Siassie Kenneally, Shuvinai Ashoona, Itee Pootoogook, and Jutai Toonoo. Supporting contemporary Inuit art provides an awareness of Inuit realities, and further expands conceptions of Canadian art.

6) Challenge Western art historical categories.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Gossip, 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection |

Pootoogook’s drawings are both familiar and foreign, making them difficult to classify within a Western art world. Her mixing of cultures creates instability, as Southern viewers connect with aspects of contemporary life, while simultaneously feeling isolated from Inuit tradition. Pootoogook’s career broke the glass ceiling for Inuit art, insisting that Inuit, female, and contemporary identities can exist simultaneously.

7) Question how we depict Indigenous artists in the media.

How is art world fame constructed, and how does it affect the artists on display?

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Sobey Award, 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook winning the Sobey Art Award in 2006 provided opportunity for the artist’s career, while also profoundly influencing her approach to the art world. The press’ invasive treatment of Pootoogook’s struggles with alcoholism and homelessness leading up to her death demonstrate the importance of representing artists with honesty and dignity.

Who creates fame for artists? For what audience? Where is the distinction between an artist’s work and their personal life?

8) Understand Pootoogook’s death within a larger context of gender-based violence.

Who creates fame for artists? For what audience? Where is the distinction between an artist’s work and their personal life?

8) Understand Pootoogook’s death within a larger context of gender-based violence.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Man Abusing his Partner, 2002. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

While the cause of Pootoogook’s death is unknown, it is important to acknowledge the thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. Pootoogook’s gender and cultural identity intersect with her experiences of violence. Sexual violence was a reality in Pootoogook’s life and art. Pootoogook’s death is a reminder that communities are continually fighting to stop violence against Indigenous women.

9) Acknowledge colonial violence and work towards reconciliation.

9) Acknowledge colonial violence and work towards reconciliation.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Begging for Money, 2006. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook’s drawings of contemporary struggles in Cape Dorset, and her experiences living in Ottawa and Montreal, demonstrate the continual existence of colonial violence. The systemic oppression of Indigenous peoples persists in Canada. Colonial oppression is something that needs to be addressed both locally and nationally. Like Pootoogook's legacy, reconciliation is an active process, as we work towards more equitable relationships.

10) Act with the belief that we can be better.

10) Act with the belief that we can be better.

|

| Annie Pootoogook, Composition (Happy Woman), 2003-2004. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Lew (2017) at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. |

Pootoogook took many risks throughout her career and embraced opportunities to further her practice. She exhibited work in Toronto, completed the Glenfiddich Residency in Scotland, exhibited at Documenta 12 in Germany, and experimented with individual objects and cinematic scale. Pootoogook did not limit her art-making to Western perceptions of Inuit or contemporary art, and neither should we. There is always more to learn.

I encourage you to visit the McMichael before Cutting Ice closes in February. Confront your own understandings of Annie Pootoogook and contemporary Inuit art. Explore how you will remember Annie, and keep questioning long past when you leave the gallery.

I encourage you to visit the McMichael before Cutting Ice closes in February. Confront your own understandings of Annie Pootoogook and contemporary Inuit art. Explore how you will remember Annie, and keep questioning long past when you leave the gallery.

Thank you for such an empathetic and insightful commentary on Annie's work and life.

ReplyDelete